Will Kymlicka is the Canada Research Chair in Political Philosophy at Queen's University. His books include Contemporary Political Philosophy: An Introduction, Multicultural Citizenship, and Multicultural Odysseys.

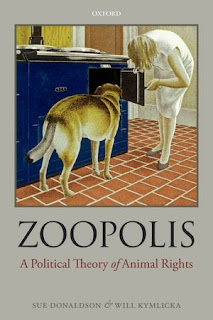

They applied the “Page 99 Test” to their new book, Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights, and reported the following:

Page 99 is the linchpin of our book. From this point forward, we develop a novel theory of animal rights, drawing on contemporary political theories of citizenship and diversity. In the human context, while we extend certain inviolable rights to all individuals simply in virtue of their humanity, we also recognize differential rights based on membership in political communities. Consider the different political statuses of citizens versus recent immigrants, foreign tourists, or refugees; or of adult versus child citizens. We argue the same logic applies to animals: all sentient animals are entitled to basic rights, but we also have differential responsibilities to particular groups of animals based on the way they are related to human political communities.Learn more about Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights at the Oxford University Press and Will Kymlicka's website.

Page 99 summarizes the limitations of previous efforts to define animal rights solely on the basis of animals’ intrinsic characteristics, or their species norms, without attention to the way they are connected to human communities. All rabbits may have the same species characteristics, but some are living in the wild apart from humans, some are feral rabbits living in urban settings, and some are domesticated rabbits raised by humans. These variations matter in ways that existing theories cannot capture, but which can be illuminated by theories of citizenship. We argue that domesticated animals should be seen as members of our community, and hence our co-citizens, whereas wild animals should be viewed as members of foreign communities, entitled to sovereign control of territory and forms of life. Liminal animals such as raccoons or pigeons inhabit an in-between position. They live amongst us, and we need to devise relationships of just co-existence with them, but the relationship is more attenuated, involving fewer mutual obligations, than co-citizenship – a status we call “denizenship”.

These relationships aren’t captured by the idea of species. They are social and political relationships determined by history, geography, mutual impacts, and mutual possibilities. And the individuals involved in these relationships are precious not just because they all share subjective consciousness, but because as individual agents they participate in and shape unique webs of relationship and possibility. As we put it on page 99:

justice requires a conception of flourishing that is more sensitive to both interspecies community membership and intra-species individual variation. It should also be open to evolution, as new forms of interspecies community emerge, opening up new possibilities for forms of animal and human flourishing…. This is precisely what is offered by a citizenship model.

--Marshal Zeringue