and of the Great Courses lecture series and short book titled Notorious London: A City Tour. He has also published multiple essays and articles on the history of education, masculinity, sexuality, fashion, hair, and dress and written on higher education pedagogy. His interests in beauty have led him to an editorial role overseeing a multivolume collection (for Bloomsbury) titled A Cultural History of Beauty. Deslandes is currently at work on a new book that examines transatlantic architectural and design exchanges between Britain and North America between the 1870s and the present.

and of the Great Courses lecture series and short book titled Notorious London: A City Tour. He has also published multiple essays and articles on the history of education, masculinity, sexuality, fashion, hair, and dress and written on higher education pedagogy. His interests in beauty have led him to an editorial role overseeing a multivolume collection (for Bloomsbury) titled A Cultural History of Beauty. Deslandes is currently at work on a new book that examines transatlantic architectural and design exchanges between Britain and North America between the 1870s and the present.

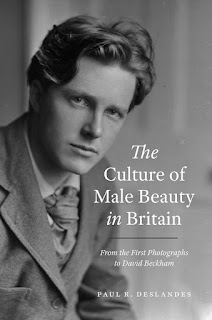

He applied the “Page 99 Test” to his new book, The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain: From the First Photographs to David Beckham, and reported the following:

Page 99 comes about a third of the way into the project’s third chapter, which is titled “Artists, Athletes, and Celebrities.” It is here that I examine how racial scientists, artists, and ardent physical culturists sought to define not only a particular vision of muscular and youthful manhood but also the peculiar abilities that late Victorian and Edwardian Britons thought they possessed to assess, judge, and categorize it. More specifically, page 99 discusses the important role that the painter Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929) played in the culture of male beauty when he captured youthfulness, litheness, and Whiteness in his depictions of sailors and young men swimming off the Cornish coast. On this page, I focus on both reviews of his work and the ways in which certain same-sex desiring men like John Addington Symonds saw, within his canvases, great aesthetic potential. A full one half of my page 99 is taken up by a Tuke photograph of two unidentified male nudes on a beach.Learn more about The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain at the University of Chicago Press website.

In my own assessment of how the “Page 99 Test” holds up in my book, I would say, fair-to-middling. The project, which chronicles the history of male beauty, male body aesthetics, and male grooming and adornment from the rise of photography in the 1840s right up to the present, is concerned with documenting the influence that individuals, like Tuke, had in articulating standards of attractiveness and encouraging Britons to be active and informed consumers of the male nude. In this way, page 99 captures an important goal of the project: to illustrate the global reach of British artistic and body culture and to showcase how representations of certain physical types informed the complex racial histories and attitudes that characterized imperial Britain. Page 99 also contains a reference to a Cadbury’s Cocoa advertisement, highlighting the role that the beautiful male face and body played in commodity culture from the Victorian era on. The photograph that takes up fifty percent of the page’s space tellingly highlights the project’s great reliance on visual culture and visual sources in narrating this revealing history.

Despite the considerable insights about my book that might be gleaned from a quick glance at page 99, some topics are left unnoted. Not present on this page is the book’s prolonged emphasis on the role that good looks played in creating commercial or professional advantages in Britain’s capitalist society or the relationship that existed between grooming, attractiveness, and the rise of the modern psychological self. Also not evidently displayed on page 99 are personal accounts of grooming rituals, articulations of sexual desire, or aesthetic responses. Absent in the book, though, they are not. These are documented in the many places where I focus on letters, diaries, and, most interestingly, data gathered by organizations like Mass Observation (in the 1930s-1940s and, again from the 1980s) and projects like the National Lesbian and Gay Survey (in the 1980s-2000s). Intended to tell this story from multiple perspectives, The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain reminds readers not only that beauty matters but also that, when its history is uncovered, it is anything but skin deep.

--Marshal Zeringue