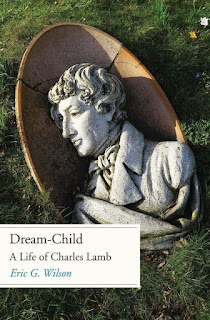

He applied the “Page 99 Test” to his new book, Dream-Child: A Life of Charles Lamb, and reported the following:

My page 99 is one of the most important in the book. It describes one of the three events that inspired my obsession with Lamb.Learn more about Dream-Child at the Yale University Press website.

This event occurred in 1796, when Lamb—twenty-one, lonely, exhausted by his London accounting job, and recovering from an unspeakable family tragedy—was frequently exchanging letters with Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge had befriended Lamb at Christ’s Hospital, a boarding school of Dickensian cruelty. The two had remained close after leaving, Coleridge on scholarship to Cambridge, Lamb—whose stutter exiled him from the oratory required for a university scholarship—to his ledgers. During December of 1794, Coleridge lived in London, and he nightly lifted Lamb from his drudgery by joining him at the Salutation and Cat to talk poetry. Then, in January, Coleridge was gone, to Bristol and marriage, and Lamb soon went insane and spent six months in an asylum.

Returned to sanity, Lamb became Coleridge’s most valued correspondent. The poet especially prized his friend’s literary criticism. On my page 99 appears Lamb’s most essential comment, from a letter of November 1796: “Cultivate simplicity, Coleridge, or rather, I should say, banish elaborateness; for simplicity springs spontaneous from the heart, and carries into daylight its own modest buds and genuine, sweet, clear flowers of expression. I allow no hot-beds in the gardens of Parnassus.” Coleridge took this seriously. He developed a new kind of verse, the “conversation” poem, in which a speaker talks to an interlocutor in relaxed blank verse. The lyrical chit-chat lifts things quotidian—like the FOMO of missing a hike—into meditations on redemption and loss.

Encouraging Coleridge toward this poetics of the everyday, Lamb pre-dated by four years Wordsworth’s ur-text of British Romanticism, the preface to the second edition of Lyrical Ballads. When I came across this largely forgotten fact of literary history, I realized that Lamb had secretly shaped a kind of Romantic poetry I really love.

What are the other two events that originated my biography? One is the unspeakable family tragedy mentioned above. On September 22 of 1796, Lamb came home and saw his beloved sister Mary standing with a knife in her hand above their bloodied and dead mother, and he bravely contrived to save her--clearly insane when she plunged the blade--from the gallows. He cared for her the rest of his life and found her, as did Coleridge, delightful when sane.

The other involves how Lamb wrote his way through his trauma. In 1820 he created a persona, “Elia,” under which he composed bizarrely charming and mirthfully melancholy essays, such as “A Chapter on Ears,” which begins, “I have no ear.”

The Page 99 Test: Eric G. Wilson's Everyone Loves a Good Train Wreck.

--Marshal Zeringue