candidates, supported women’s causes as a leader in the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Women’s Campaign Fund, educated students, and motivated audiences to take up the banner.

candidates, supported women’s causes as a leader in the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Women’s Campaign Fund, educated students, and motivated audiences to take up the banner.

Griffith's biography of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, In Her Own Right (1984), was named “one of the 15 best books of 1984” and “one of the best books of the century” by the editors of The New York Times Book Review and “one of the five best books on women’s history” by the Wall Street Journal in 2009. In March 2020, Oprah magazine recommended it for women’s history month reading. It inspired Ken Burns’ PBS documentary, Not for Ourselves Alone, on which she served as a consultant.

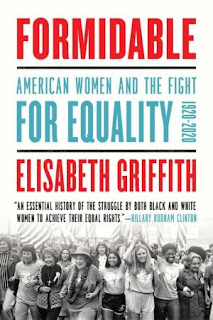

Griffith applied the "Page 99 Test" to her new book, Formidable: American Women and the Fight for Equality: 1920-2020, and reported the following:

Page 99 of Formidable appears four pages into chapter four, “From Rosie to Rosa Parks, 1945-1959,” which covers the forced retirement of women working in war industries to make room for returning veterans, who were eager to start families. It introduces the baby boom and the voluntary isolation of white women into segregated suburbs, while Black women continued to fight racial discrimination in education, housing, jobs, and juries. While page 99 mentions Christian Dior’s “New Look,” crinolines, long-line bras, cinched waists, charm bracelets, and French bikinis (named for a Pacific atoll which was an atomic bomb test site; women brave enough to wear them were called “bombshells”), its theme is not fashion. It’s about the physical and psychological containment of women. The first line on page 99 recalls Wonder Woman having a nightmare, dreaming of becoming Steve Trevor’s “docile little wife.” The pressure on white women to conform to a new cult of domesticity wa part of the country’s effort to contain communism, curb racial conflict, condemn homosexuality, and defend the “American way of life.”Visit Elisabeth Griffith's website.

While page 99 is not the ideal introduction to the subject of my book, the century-long fight for equal and civil rights, by a diverse cast of female change agents following passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, it illustrates the variety of elements that contributed to that struggle, including comic book heroines and girdles. Women were historically confined to a female sphere of activity and criticized whenever they moved beyond their traditional maternal and domestic roles. To win the vote, even single suffragists relied on the moral authority of motherhood to make the case that the country needed good housekeepers. In the 1920s, many states had laws barring married women from working without their husband’s permission. In the 1930s, the federal government forbade the employment of the wives (but not the children) of its male employees. Those restrictions were removed when World War II required more factory workers, pilots and code breakers, but they returned in peacetime. In contrast, while Black women confronted racial violence and daily discrimination, the men in their communities respected and encouraged their political engagement. As teachers, housekeepers, public health nurses, agricultural agents, and church deacons, they kept working, quietly, in church basements and behind the scenes, to advance civil rights and end segregation. By the end of the 1950s, the work of Constance Baker Motley, Rosa Parks, Ella Baker, and Daisy Bates would inspire many white women to reignite their struggle for equal rights, as Black and white abolitionists had spurred the suffrage movement.

Patriarchy, the root of sexism and racism, remains powerful. No matter how far all American women have advanced in the past century, they remain victims of rape and violence, at risk of maternal death, underpaid in the workforce, undervalued in their caregiving roles, under represented politically, and without reproductive rights and agency. Formidable describes the strides women have made, the tensions and issues that have divided them, and the challenges and opposition that remain. It also offers models of courage and resilience, to inspire readers to keep up the fight.

--Marshal Zeringue