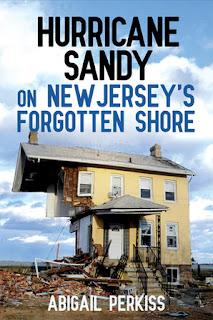

collection of oral history interviews that she and her students collected between 2013 and 2016 to tell the story of Hurricane Sandy and its aftermath on New Jersey’s Bayshore. These interviews, individually and collectively, offer a portrait of a devastating storm, and of the network of relationships as victims, volunteers, and state and federal agencies came together to rebuild in its wake.

collection of oral history interviews that she and her students collected between 2013 and 2016 to tell the story of Hurricane Sandy and its aftermath on New Jersey’s Bayshore. These interviews, individually and collectively, offer a portrait of a devastating storm, and of the network of relationships as victims, volunteers, and state and federal agencies came together to rebuild in its wake.

Perkiss applied the Page 99 Test to Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore and reported the following:

From page 99:Visit Abigail Perkiss's website.In many critical ways, this project was highly particularized; it was born out of a unique combination of circumstances, relationships, and personnel, and it was supported by a variety of institutions at every step of the development process. The early and continued commitment from [a variety of stakeholders] led to the creation of an important community oral history project and, no less significant, the development of a new and emerging group of oral and public historians, trained and practiced in oral history and digital humanities methods. This distinctive set of resources came together to create the possibility for meaningful oral history work where the whole was much greater than the sum of its individual parts.Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore is a slim volume; page 99 comes in the appendices – specifically, from an essay about the origins story of a longitudinal oral history project in which my students at Kean University and I conducted more than seventy interviews, documenting the uneven relief and recovery efforts after Hurricane Sandy collided with the New Jersey coastline in 2012.

At the same time, this project reveals the potential that arises when institutions come together to pool their financial, experiential, and temporal resources toward a collective end. Oral and public history work is built on collaboration, creativity, and adaptability in the face of limited time and personnel and increasingly diminishing financial support. Staring Out to Sea [the title of the oral history project] offers a model for the ways in which individual agencies and organizations can come together to support the development of new and innovative projects that serve the interests of both public historians and the communities with which they work. Taken to scale, this project offers the framework for ongoing, sustainability oral history work at all levels of the profession.

On its face, page 99 is ancillary to the essence of Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore. The book chronicles the story of Sandy and its aftermath along the 115 miles of coastline, from Sandy Hook at the lip of the Atlantic Ocean to South Amboy at the mouth of the Raritan Bay: New Jersey’s Bayshore.

At the same, page 99 reveals the very foundation on which this book was built. The oral histories my students and I collected between 2013 and 2016 form the narrative backbone of Hurricane Sandy on New Jersey’s Forgotten Shore. These interviews reveal intimate window into the human impact of a devastating storm and the intended and unintended consequences of long-term policy decisions that created the conditions for such destruction.

The experience of Sandy for those who make their lives on the Bayshore offer insight into how we prepare for, survive, and respond to disaster. These experience at once lay bare the human toll of disaster and the human capacity for resilience. Collette Kennedy, who moved to Keyport just weeks before Sandy hit, was so looking forward to celebrating her first Halloween in her new home. Linda Gonzalez penned poems by candlelight as rain and wind beat down on her beloved Union Beach, knowing that those might be the last moments of relative calm that she would experience for months. James Butler erected a washed-up plastic Christmas tree at the corner of Jersey Avenue and Shore Road and became a national icon representing “Jersey Strong.” And Mary Jane and Roger Michalak, married forty-seven years, realized that they wouldn’t be able to raise themselves through a hole in their attic and instead sat down on their bed together, waiting for the water to wash over them. These voices, individually and collectively, offer a portrait of a devastating storm and of the network of relationships as suvivors, volunteers, and state and federal agencies came together afterward to rebuild.

--Marshal Zeringue