The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Fides et Historia, and The International Journal of Christianity & Education. In addition to lecturing in the History Department at Baylor University, Gutacker serves as director of Brazos Fellows, a post-college fellowship centered on theological study, spiritual disciplines, and vocational discernment.

The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Fides et Historia, and The International Journal of Christianity & Education. In addition to lecturing in the History Department at Baylor University, Gutacker serves as director of Brazos Fellows, a post-college fellowship centered on theological study, spiritual disciplines, and vocational discernment.

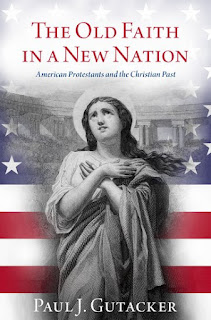

He applied the "Page 99 Test" to his new book, The Old Faith in a New Nation: American Protestants and the Christian Past, and reported the following:

From page 99:Follow Paul J. Gutacker on Twitter.One reviewer who highlighted Child’s conclusion still missed its gendered implication. John A. Gurley, a Universalist pastor and editor of the Cincinnati newspaper Star in the West, worried that Child’s history “will prove a source of much injury to the cause of Christianity, by multiplying skeptics, especially among her own sex.” Gurley insisted that genuine Christianity had nothing to do with the corrupt traditions that Child traced. “Romanism and Calvinism are not Christianity,” Gurley explained. “Here is where Mrs. Child mistakes. Human creeds, filled with the omnipotent wrath of God, and endless hell torments, are not Christianity. To find Christianity we must find Christ. Christ, the gentle, the lowly, the compassionate.” Child, of course, had described Christ in these terms and named them feminine—a point that Gurley failed to notice even as he worried about Child’s account damaging the faithful hope of pious women.Yes, page 99 gives a fairly good idea of the book.

Child was not the only woman whose work was misread by contemporary reviewers. Hale’s Woman’s Record, which opened this chapter, intended to show the importance of education, opportunity, and advancement for women. But if Hale hoped to show the historical significance of her sex, male reviewers read her book as proof of their own superiority. The Evening Post took its review of Woman’s Record as an opportunity to belittle women: “From the creation to the present day . . . the 5,857 years which have passed have only bequeathed to us 2,500 distinguished women—less than half a distinguished woman per annum.” The review suggested that many of the women included hardly deserved such commendation, pointed out that even the “most brilliant . . . are sadly behind their masculine rivals,” and speculated that a work that compiled every distinguished man since creation would make the woman’s record appear a trifle.

The reason this page “passes the test” is that it summarizes several reviews written by men about books written by women. These women (Lydia Maria Child and Sarah Josepha Hale, respectively) were for their part producing innovative accounts of the history of Christianity that foregrounded their sex’s contributions to that history. These reviews reveal a major theme of the book, which explores how American readers and authors engaged with the Christian past—how they remembered and used that past toward various ends. It also shows male reviewers being relatively dismissive of these books, evidencing how much the remembered history of Christianity was a story about men and their achievements. In other words, this page illustrates the ways in which the Christian past was created, contested, and employed in nineteenth century America.

--Marshal Zeringue