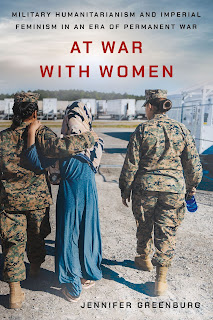

She applied the "Page 99 Test" to her new book, At War with Women: Military Humanitarianism and Imperial Feminism in an Era of Permanent War, and reported the following:

If you open to page 99 of At War with Women, you are teleported to a simulation of Afghanistan on a US military base. A US Army officer is lecturing his troops about how they need to get better at making small talk with the Afghan villagers (here played by hired actors). This is important to win the so-called “battle for hearts and minds” in counterinsurgency—the military strategy at the time that allegedly focused more on winning the population’s support than eliminating the enemy. The officer encourages the soldiers to ask the villagers what kind of tea they are drinking or ask about some part of the landscape. Across the room, the head of security tells his team “you’ve got to look like you’re ready for a fight. Aggressive. Ready to go.”Visit Jennifer Greenburg's website.

The Page 99 Test works well in this case because it shows the contradiction of being what one soldier earlier in the book calls “an NGO with guns.” We see how the security force is trained to be “aggressive” and “ready to go” but in this period of the post-9/11 wars they were also supposed to carry out surveys of village needs so that the military could build schools or wells to “win hearts and minds.” On this page, we also meet Sean, a pseudonym for one of the only marines in the book who is excited about doing more civilian-oriented military tasks. Earlier in this chapter, we see how other marines feminize Sean through his association with “softer” tasks such as interacting with civilians. One of the book’s key arguments is that the military’s turn to counterinsurgency unintentionally reinforced conventional associations of combat with masculinity. We see how this happens on page 99 through the contractors who are in the simulation to teach the military how to adopt development tactics as part of their counterinsurgency doctrine. Military audiences feminize the contractors and their academic, civilian-focused material. This chapter is about how soldiers and marines come to reject the idea that they should be more like “armed social workers” on the basis of the tensions and contradictions playing out on page 99.

The page ends by stating, “The simulation also provided a window into how the canals the military team considered building were not nearly as significant an effect of the training as the shifting notions of race and gender within the DSF” (the DSF is the “district stability framework,” or the development framework contractors were teaching the military). At War with Women is about how these shifting notions of race and gender were produced through a key turning point in the post-9/11 wars. Page 99 is part of a story about how military trainings like the one on this page did not accomplish their stated aims, but they did produce enduring racist and imperialist understandings of Afghan people as children incapable of taking care of themselves. As headlines these days are more likely to cover dire poverty and insecurity in Afghanistan than the wars that produced these conditions, we would do well to consider the origins of such representations of Afghanistan and what a productive way forward might be.

--Marshal Zeringue