Quirke applied the “Page 99 Test” to her new book Eyes on Labor: News Photography and America's Working Class, and reported the following:

Quirke applied the “Page 99 Test” to her new book Eyes on Labor: News Photography and America's Working Class, and reported the following:Eyes on Labor: News Photography and America’s Working Class brings together two revolutions of the twentieth century: American workers’ epic struggle to achieve security through unions, and the virtual explosion of imagery in the news. (Not until 1942 was a Pulitzer awarded to a photograph—one sign that the medium had arrived!) Organized labor and corporations both harnessed news photography’s modern vitality and its apparent objectivity to make competing claims about workers and their unions.Learn more about Eyes on Labor at the Oxford University Press website.

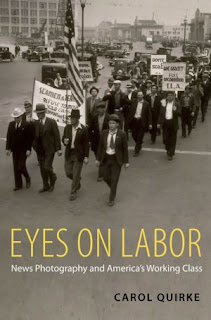

The book’s cover suggests a conventional tale of industrial workers: white men, on the streets, demonstrating and striking for union representation. There was no right to a union in 1934, when the cover photo of the San Francisco general strike was taken. The National Labor Relations Act had not yet passed, and workers had not secured the law’s guarantees for themselves, as many corporations ignored the law until WWII. Page 99 [below] on the other hand, with its photos of unionists cavorting at a camp in the Catskills, redefined how Americans saw labor. The photos, from a 1938 LIFE magazine photo-essay about the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, make unionists look just like the youth and college co-eds that LIFE embraced as part of its portrait of the American good life.

The “page 99 test” points to the unexpected complexity of labor’s representation, which Eyes on Labor explores. The book charts labor’s portrayal from the late nineteenth century with the 1892 Homestead strike, to the 1911 Triangle Fire, to the 1919 strike wave. It analyzes LIFE along with two union newspapers, one of which had an unusual worker-run camera club. The book also addresses coverage of the infamous 1937 Memorial Day Massacre where police shot over a hundred demonstrators in Chicago, and a little studied strike at the Hershey Chocolate Company that catapulted into national news attention because of photographic evidence. Labor’s status was renegotiated in front of factories, before government officials, and in union halls and corporate boardrooms. But struggles over labor’s possibilities transpired in the pages of a national and visual news. News photos propelled workers into the American mainstream—workers were no longer “the other half.” But labor’s contradictory portrayal constricted, as well as widened, its potential. Photographs promoted rank-and-file passivity, divided workers amongst themselves, and narrowed the vision of unionism’s rewards. Today less than twelve percent of American workers are unionized—a historic low. Workers’ representation contributed to their political weakness.

--Marshal Zeringue