There You Have It: The Life, Legacy, and Legend of Howard Cosell and To Show What an Indian Can Do: Sports at Native American Boarding Schools, among other books.

There You Have It: The Life, Legacy, and Legend of Howard Cosell and To Show What an Indian Can Do: Sports at Native American Boarding Schools, among other books.

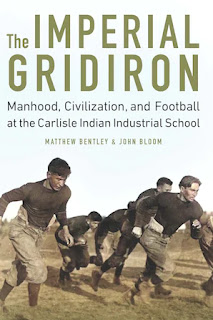

Bloom applied the "Page 99 Test" to their new book, The Imperial Gridiron: Manhood, Civilization, and Football at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and reported the following:

On page 99 we discuss some of the prominent athletes, such as distance runner Louis Tewwanima and Jim Thorpe who emerged from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School to represent the United States as medalists in the Olympics.Learn more about The Imperial Gridiron at the University of Nebraska Press website.Tewanima first came to Carlisle as a prisoner of war. The Army had taken him from his family and clan, enforcing federal orders that had sided with Mormon farmers in a land dispute. Tewanima foreshadowed future people of color who competed successfully for the United States on an international stage, sports figures who have brought laurels to a nation that has systematically oppressed them. In fact, in the case of Tewanima during the 1912 Stockholm games, the United States was still twelve years away from granting Native Americans citizenship. Yet Tewanima and other Hopi runners always saw themselves as representing more than just one nation. In the words of historian Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, “Americans considered Tewanima to be their trophy of colonization,” but his “desire to join Carlisle’s track team and his participation in marathons was deeply rooted in who he was as a Hopi runner for the Bear Strap Clan.”Located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School was created by the federal government in order to force assimilation upon Indigenous Americans. It was a violent project whose founders showed no respect for or recognition of Indigenous societies, art, or stories. Football became an important tool that the school’s administration used to promote its mission to the nation at large. Ideas about gender were central to their use of the sport and to their ideas about assimilation.

On the football gridiron and in the world of track and field, however, no player achieved greater fame and stature than Jim Thorpe. Few athletes anywhere in the world have ever demonstrated Thorpe’s versatility. He played for and starred for Carlisle between 1907 and 1912, helping to guide the team to twenty-three wins over his final two years, including victories over Harvard and the Army. He won gold medals for the modern pentathlon and decathlon in the 1912 Olympics. He had a twenty-year professional baseball career and was a founding member of the professional football organization that became the National Football League.

Students came to Carlisle from over 140 different Indigenous nations, each with distinct rituals, identities, and cultural formations associated with human sexuality and gender. At the school, they encountered a curriculum and disciplinary code that narrowly defined their gendered identities within a Victorian discourse of manhood and womanhood. This gender socialization was central to the way that the school hoped to conquer their souls. School administrators like the institution’s founder, Richard Henry Pratt, believed that Indigenous men needed to become “civilized” gentlemen. These white educational leaders believed that Indigenous males were too “masculine.” In other words, they believed that Indigenous men were too physical and too much tied to what they saw as the elemental, violent, and aggressive aspects of male character. Meanwhile, elite white young men attending colleges began to develop a cult of masculinity, one that rejected gentlemanly manners and embraced physical toughness. They created and played the exceedingly violent game of football as an expression of their newfound enchantment with all things masculine. Alternatively, Pratt hoped that if young Indigenous men from Carlisle could play the violent game of football as gentlemen, they could promote his Pygmalion vision, and that he, as the school’s visionary, would silence his doubters.

As our Page 99 Test reveals, we don’t get to a discussion of the most famous Carlisle athletes until page 99 of our book. This isn’t to diminish the importance of these athletes. In fact, as the passage illustrates, we try as much as we can not to discuss them as, in the words of Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert “trophies of colonization.” Instead, as in this passage, we hope to present their athletic success in terms of the identities that the Carlisle Indian Industrial School attempted to strip from them.

--Marshal Zeringue