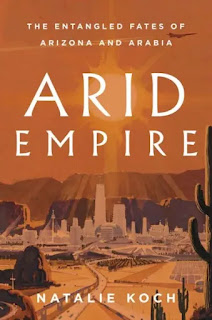

Koch applied the "Page 99 Test" to her new book, Arid Empire: The Entangled Fates of Arizona and Arabia, and reported the following:

From page 99:Visit Natalie Koch's website.The earliest technological advance in the cultivation of Arizona and Arabia’s arid landscapes were wells that could be pumped electronically, replacing the slow and expensive animal-powered methods of the past. In Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Arizona alike, clever canal systems could divert water to crops far from the original source. Extracting freshwater from wells and canals was still limiting, though. The real promise of limitless water is in the ocean. Optimistic engineers, farmers, and seafarers have long sought ways to make saltwater usable through desalination—that is, stripping out the salt. Water desalination is an ancient practice, based on various techniques of distillation. European explorers began trying to modernize it in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, when they installed emergency desalting devices for their long ocean voyages. The practice was later expanded aboard steamships in the 1840s and 50’s and quickly transformed into land-based desalting facilities built around steam condensers.The text works well for my book because it launches the reader into one of the most important themes in how “arid empire” works –people harnessing new technologies to source water in the desert.

The Page 99 Test is interesting because it opens up the bigger issue about how people have historically thought about finding ways to live and grow food in the desert. I am from Tucson, Arizona, so the limited water resources of a desert was something I grew up learning about. But I didn’t know the deeper history of how commercial agriculture systems were developed in Arizona, and I certainly didn’t know how connected they were to places in the Arabian Peninsula. The chapter that this page comes from talks about a University of Arizona project in Abu Dhabi (now, the UAE) in the 1960s and 70s. I had been traveling there for years before I discovered the history of project from over 50 years before. And almost no one in the UAE had ever heard of it, and even few people in Arizona know about it. The book repeatedly comes back to the question that kept pursuing me in all the research: why is this history so invisible today? Over the several years of researching this book, I became obsessed with chasing the hidden stories that I go into – ranging from the camels (and camel herders!) imported to help settlers take over the new desert territories added to the US after the Mexican-American War in 1848, to the date palms imported to set up a US date industry in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Biblical fantasies of the “Old World” deserts were central to the early settler visions of colonizing the “New World” deserts the US Southwest, but they quickly gave way to fantasies of using new technologies to master and “civilize” the desert environment, which becomes the real focus of arid empire in the US. The quote from this test doesn’t get into all that, but it starts to introduce that transition in the history I trace over 150 years.

--Marshal Zeringue