and religion and Howard W. Hunter Chair in Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University, where he teaches courses in American history, new religious movements, religions of North America, and Mormonism.

and religion and Howard W. Hunter Chair in Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University, where he teaches courses in American history, new religious movements, religions of North America, and Mormonism.

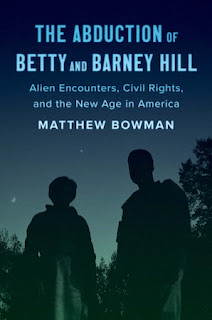

Bowman applied the “Page 99 Test” to his new book, The Abduction of Betty and Barney Hill: Alien Encounters, Civil Rights, and the New Age in America, and reported the following:

Page 99 of The Abduction of Betty and Barney Hill does not, unfortunately, mention Betty and Barney Hill. Nor does it mention their story of alien abduction, which is the broader narrative the book explores. Rather, this page is part of a brief exploration of the career of Morey Bernstein, a salesman who took up hypnosis as a hobby. In the early 1950s, he began hypnotizing a housewife named Virginia Tighe, and was astonished when the woman began speaking in an Irish brogue and describing her life as Bridey Murphy, the wife of an Irish lawyer who died in Belfast in 1864. Bernstein was nothing if not a shrewd capitalist, and this page describes his transformation of Tighe's story into a bestselling book, followed quickly by a movie adaptation.Visit Matthew Bowman's website.

The story made Bernstein rich. A hypnosis craze swept the nation in the 1950s. It became a popular party trick and a common subject for popular films and novels. But Bernstein also drew critics. A slew of professional psychiatrists and other counselors who used hypnosis warned that neither hypnosis nor memory worked the way Bernstein alleged - human memories are not like gems to be unearthed from the soil of our minds; rather they are constructed in the process of recall. Hypnosis, then, is not simply a shovel for the unearthing, but can actually influence the memories constructed.

Despite not mentioning Betty and Barney, this section is critical both to the way I imagined the book and the sort of argument I wanted the book to make. Betty and Barney Hill saw a strange light in the sky while driving to their New Hampshire home one September night in 1961. In 1964, under hypnosis, they experienced memories of being abducted by creatures from that light and subjected to medical tests before being returned to their car having forgotten it all.

While on the face of it this seems an incredible story, my purpose in the book is to embed it in the culture of the American mid-century, to show how the HIlls's story reflected and was absorbed by other cultural trends. Like, for instance, the growing fascination with psychiatry and hypnosis, the explosion of therapy as a profession and a practice, and the awe with which many Americans approached science.

Betty and Barney Hill's recovered memory led them into many other mid-century cultural conflicts. It became fodder in the struggle for civil rights, as the Hills were an interracial couple deeply involved in the Black freedom movement. It led them out of the conventional liberal politics they shared with many other Americans and toward the New Age and conspiracy theory. But they were able to travel such paths because others, like Morey Bernstein, paved the way.

--Marshal Zeringue