Wandering Greeks, and Athens Burning. He has also recorded six courses for the Great Courses, most recently God against the Gods.

Wandering Greeks, and Athens Burning. He has also recorded six courses for the Great Courses, most recently God against the Gods.

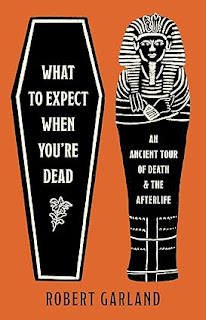

Garland applied the “Page 99 Test” to his new book, What to Expect When You're Dead: An Ancient Tour of Death and the Afterlife, and reported the following:

Page 99 just so happens to be a half-page, headed by the words of the Stoic philosopher Seneca, "Life is just like a play. It doesn't matter how big the part is. It's how well you act it." I wholeheartedly agree. The page also just so happens to fall at the beginning of the chapter entitled "Heaven and Hell," and if there's one very big question that the book raises - apart from whether there is an afterlife - it's how the idea of Heaven and Hell first seeped into the human imagination.Learn more about What to Expect When You're Dead at the Princeton University Press website.

Page 99 stands at the beginning of a journey of exploration to discover how ancient civilizations first came up with the idea of a dualistic afterlife - the otherworldly other worlds that we tend to call Heaven and Hell, which play such a major role in Christian and Islamic thinking. However, it also points out that these alternative universes did not arrive overnight and "were not central to what most ancient peoples imagined to be the afterlife awaiting them." Page 99 also anticipates speculation about that ever-fascinating and perplexing question as to how we will experience pleasure and pain in the world to come, and what we will actually be able to do when we're dead, the answers to which of course depend on whether we will have physical bodies with appetites and desires or whether we will exist in some disembodied form, not to say whether we will even exist at all, which the following chapter will explore. The page references many of the ancient peoples whose ideas feature throughout the book - the Egyptians, Etruscans, Greeks, Mesopotamians, and Israelites, along with the Romans, Early Christians, Hindus, and Muslims, including, at the very beginning of this ancient tour, our distant ancestors, the Neanderthals, who were the first people to practice intentional burial, and who may also have already come up with the idea that death may not mean extinction.

What to Expect When You're Dead offers an animated and lively cross-cultural survey of death practices and beliefs about the afterlife. Its approach is to underscore the essential uniformity of those practices and beliefs, while at the same time emphasizing important and striking variants. This, as it turns out, is exactly what is illustrated on page 99, where the point is made that whereas the Egyptians envisaged the afterlife as a continuation of life on earth, the Greeks initially consigned all their dead to the dreariness and darkness of Hades. Studying what people did thousands of years ago connects us with our cultural ancestors, all of whom without exception asked exactly the same question that we do: is there indeed anything to expect when we're dead? The tone of the book is essentially light-hearted, even uplifting. After all, there's no reason why studying death should be a downer. Mortality and the mortal condition, irrespective of any hope of an afterlife, are precisely what make life so infinitely precious.

The Page 99 Test: Wandering Greeks.

--Marshal Zeringue