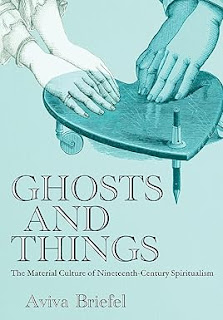

Briefel applied the "Page 99 Test" to her new book, Ghosts and Things: The Material Culture of Nineteenth-Century Spiritualism, with the following results:

I was relieved to find that page 99 captures the book as a whole: it introduces the concept of “exposure,” which I argue was essential to the cultures of Victorian spiritualism and skepticism. (Understandably, I had been somewhat nervous that my book itself would be exposed as failing the Page 99 Test.) One of the recurring themes of Ghosts and Things describes the complex interactions that occurred between those who adamantly believed that material objects could be used to communicate with ghosts during séances and those who were ready to expose spiritualists as frauds.Learn more about Ghosts and Things at the Cornell University Press website.

Page 99 initiates a discussion of how the concept of exposure was applied to the Davenport Brothers, American spiritualists who claimed to be able to interact with spirits by using a wooden cabinet. During their public séances, the brothers sat in the cabinet, which also contained a selection of musical instruments, and asked audience members to tie them with ropes and shut the doors. Spectators would witness spirit manifestations emanating from the closed cabinet, including musical instruments playing and spectral hands reaching out of the cabinet’s aperture. After a while, the doors to the cabinet swung open and the brothers could be seen, freed from their ropes, allegedly through the intervention of spirits. These feats led the Davenports to become renowned mediums in the United States and Britain. On page 99, I preview the various types of exposure that would befall the brothers a few months after journeying to England in 1865, both through the destruction of their cabinet during performances in Liverpool, Huddersfield, and Leeds, and through the appropriation of their trick by “anti-spiritualist” magicians who used their own versions of the cabinet to discredit the brothers.

Both of these strategies for exposing the Davenport Brothers reveal the tenuousness of the term “exposure” itself. When an angry audience rushed the stage and destroyed the cabinet on February 15, 1865, at St. George’s Hall in Liverpool, they did not find any hidden mechanisms or tricks. And yet, newspaper headlines announced the “Defeat and Exposure of the Davenport Brothers,” raising the question of what exposure without proof of fraud might mean. Given that the Davenports’ humiliation emphasized the breaking of the cabinet, does the term take on other meanings, such as an “exposure” to the elements? Or does it represent a loss of value through an unpackaging, not dissimilar to what happens now to action figures or dolls when taken out of their original containers? Likewise, the repetition of the Davenports’ acts by anti-Spiritualists such as Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin and John Nevil Maskelyne also signal the instability of the idea of exposure. The replication of cabinets on stages throughout Europe and the United States blurred the line between homage and parody, as well as between the role of skeptics and believers in spiritualism, one of the main claims of my book.

In the rest of the chapter, I discuss the ways in which the Davenports themselves might have eventually been subject to yet another form of exposure. I contend that it is possible they borrowed their act from Henry Box Brown, who famously escaped from enslavement in March 1849 by arranging to have himself shipped in a wooden container from Richmond to Philadelphia. He subsequently went on to reenact this feat in front of audiences, including in England, when in May 1851, he traveled in his original box by from Bradford to Leeds, to the acclaim of large audiences. He later undertook his own anti-Spiritualist performances, seeking to expose the Davenport Brothers, which I argue might point to another meaning of exposure, this time of the brothers’ secretive adoption of a “gimmick” that Brown himself had devised. The dizzying significations of the term “exposure” are one example of the ways in which spiritualism offered new terminologies for grasping the visible and invisible worlds of Victorian culture.

--Marshal Zeringue